Chinese industrial policy deftly combines state guidance and market mechanisms. By further blurring the lines between state-support and market-forces, Beijing has made it even more difficult for economic partners to assess subsidies of various forms.

Longing after the manufacturing might displayed by Germany’s hidden champions, Chinese policy, think tank and investment banking documents regard them as a model to emulate. The German hidden champions concept has been developed by German management theorist and consultant Hermann Simon to explain the success of German SMEs in global markets. These firms emerged organically from the economic and social circumstances present in Germany, such as excellent vocational training, close ties to social banks, and a distinctive corporate culture. Beijing thinks that it can replicate their success through state intervention, essentially turning a bottom-up process on its head. The very different social and economic environment in China means that it is down to government officials to orchestrate the emergence of local hidden champions. Hence the cultivation system has been set up to identify potential success stories and channel state support.

High-tech small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have emerged as key new players in China’s industrial policy: They have the potential to specialize in niche markets, develop domestic alternatives to foreign inputs and reinforce China’s industrial chain. Beijing has established a comprehensive support system for these firms, as originally outlined in the Made in China 2025 strategy.

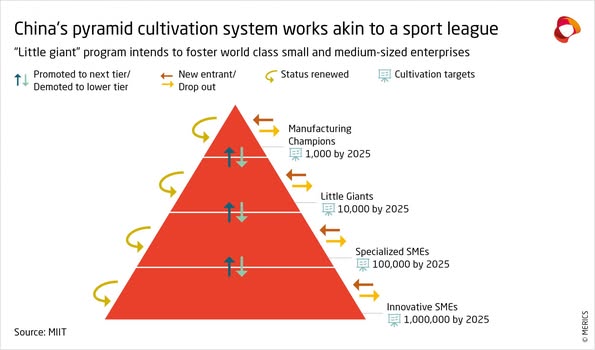

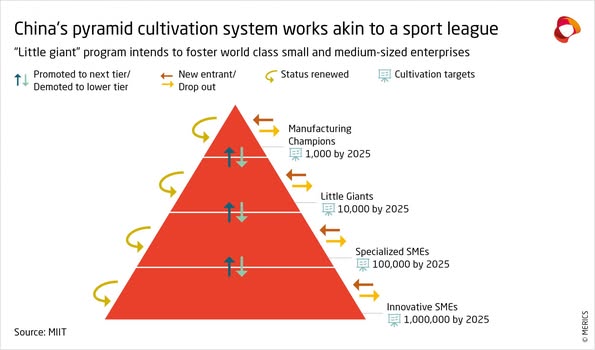

The emergence of an “accelerator state” in China marks a dramatic extension of the industrial focus of Chinese policymakers towards smaller companies: It works in four steps: In first step 1 million innovative SMEs are identified on the basis of their area of work and given state funding and state help. In second step among 1 million, 100, 000 specialized EMEs are selected and given more state funds and backing. Among 100,000 specialized EMEs, 10,000 Little Giants are selected who are given not only more state funding and backing but also help from private investors and stock market. From 10,000 Little Giants, 1,000 Manufacturing Champions are endorsed.

Previous industrial policy primarily directed resources to larger firms to achieve strategic goals. Smaller firms are now seen as valuable sources of innovation. This is because smaller firms usually thrives on individual urge/dream to innovate rather than profit. The government uses selection criteria to choose Little Giants and other types of high- tech SMEs. Officials at the municipal and provincial levels rely on them to evaluate and pick companies which they then recommend to higher authorities for further support. The criteria are broad in scope and cover aspects such as niche product focus, growth performance, the number of invention patents and R&D intensity. Out of a sample of 44 robotics firms selected in the first two batches of the Little Giants program, many appear to fall below the selection standards or to undermine its objectives.

Beijing’s tiered-cultivation combines state guidance with market forces: China has developed a dynamic multi-level evaluation and support system, active at the local, provincial and national levels, to first identify specialized high-tech SMEs and then fast-track their growth. This means companies are evaluated on the basis of use-value rather than exchange-value. So companies must fulfill technological conditions to get state investments. Profit is not the criteria for getting more investment.

Government-certified high-tech SMEs are labeled as “Specialized SMEs” or “Little Giants”: They benefit from a comprehensive system of direct and indirect state support. But these firms cannot rest on their laurels as the system is set up to promote competition and after three years the government support has to be earned once again. So the firms are now competing for more state funds after three years. To score high in competition firms must fulfill government given criteria of production. Again profit is not the focus for getting investment.

Officials are channeling ever more finance towards high-tech companies: Beijing has mobilized public financial institutions and is pushing private investors to direct capital towards government-certified start-ups and SMEs, worth tens of billions of yuan. The government has increased loan financing through the banking system and expanded access to equity markets for high-tech SMEs.

The support system seeks to cover all the needs of its SMEs: The government is encouraging all state-connected entities to help high-tech SMEs. This means more state subsidies and R&D support, increased collaboration with universities and research institutes and a more favorable intellectual property system. Officials are also directing large firms to act as financiers, clients and mentors. Big companies are not allowed to buy out successful SMEs. Here again, state is creating hindrances in centralization of production.

The model's Success: The system is channeling more funding to high-tech SMEs. Several state-backed firms such as Leaderdrive and Endovastec in the robotics and MedTech sectors are advancing self-reliance in core technologies.

The Model's Weakness: Yet, there are also signs of weaknesses. The system relies on the capacity of officials to identify the most promising firms, which may be flawed. Support measures could result in significant bad investments and misuse of funds.

The Model's Speciality: Little Giants are increasingly viewed as sound investment options. According to Bloomberg, one venture capital firm only invests in Little Giants.30 Numerous bank reports also highlight Little Giants as aligned with government policy and displaying strong growth potential. So state given certificates are drawing in foreign investments too besides state investments. But private investments show that private players believe the certification processes and evaluation systems.

To be included in the Little Giants program, companies must operate in one of ten priority sectors from the “Made in China 2025” plan. These include computer numerical control (CNC) machining, electric vehicles, or medical devices. Additional evaluation criteria include a company's potential to replace imports or to secure a significant global market share in innovative niche products.

These are government-backed firms which benefit from increased cooperation with large companies, to help them fill supply chain gaps, as well as with universities on research and development (R&D). They are supported in intellectual property rights – and, above all, financially supported. The state acts as a patient investor to early-stage high-tech SMEs by leveraging government guidance funds and through favorable loans from state-owned banks, which serve "Little Giants" in specially created departments.

Companies can also more easily raise capital on the stock markets thanks to simplified listing requirements. In 2022, 40 percent of listings on the Shanghai, Shenzhen and Beijing stock exchanges were made by Little Giants. For example, in September, Hubei Kait Automotive raised CNY 133 million (around EUR 15 million) during its IPO in Beijing. The supplier of automotive electronics and sensors counts Chinese automaker BYD and Volkswagen among its customers.

Numerous Little Giant firms are contributing to China's rise in the e-mobility sector. Guizhou Anda produces battery materials for major battery manufacturers such as CATL, BYD, and CALB. The company was listed on the Beijing stock exchange in March 2023, raising CNY 650 million (around EUR 88 million). Welion, a provider of high-performance solid-state batteries, is rapidly expanding its production capacities and plans to go public by 2025. The company has already won Nio as a customer and has reportedly attracted interest from companies like Volkswagen and Mercedes-Benz.

The Europeans could lose market share in China and globally. The EU’s exports to China are worth EUR 230 billion in total and are heavily concentrated in machinery, vehicles and other manufactured goods. About 40 percent of that could be threatened by Chinese competitors.

Foreign companies producing in China are less vulnerable to China's efforts to secure supply chains. However, domestic competition is growing, especially in sectors that China defines as strategically important, such as mechanical engineering, an area where German companies are especially active.

China's ambitious high-tech SME program ought to be a wake-up call. In many areas, the times when European companies enjoyed a clear technological advantage in China are coming to an end. Europe’s automotive sector, especially in the field of electric vehicles, has already experienced a rude awakening. Now Europe’s Hidden Champions could be next.

[Reference: https://merics.org/en/report/accelerator-state-how-china-fosters-little-giant-companies?fbclid=IwY2xjawIxWVFleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHWjKwgWyKSeBRK4HT11Xg9wZ0Dd41vta802Fb1wcctwSkYAXm0v8ds7pJw_aem_Frr5mVCBNBcbWJsdk4stUQ ]

Author: Saikat Bhattacharya